by Enrico Tuccinardi

Translated from the French and edited

by René Salm

Eleazar ha-Kalir

To understand the significance of Avi-Yonah’s reconstruction, we must briefly consider the oldest previous mention of Nazareth in the literature. This was the Lamentation for the 9th of Ab by the poet Eleazar ha-Kalir. Kalir is one of the most ancient and celebrated Jewish liturgical poets. He lived in Israel at an undetermined date in Byzantine times (VIII-IX CE) and authored over two hundred hymns serving as ritual synagogal prayers. The piyyoutim,6 especially those of Kalir, frequently refer to numerous midrashim and were often written in an allusive and even cryptic style.

In the mid-19th century, Rabbi Y. S. Rapoport (1790-1867), a learned Jew, made a significant discovery. Samuel Klein (p. 5) writes:

In 1841, the brilliant researcher S.J.L. Rapoport noted that Eleazar ha-Kalir… provided a residence-list for the priestly courses [families] of the Second Temple Period in one of his poems for the 9th of Ab, making use of halachic and haggadic literature, and that ha-Kalir had used a collection of now lost baraitoth as its source…

Ha-Kalir’s Lamentation has twenty-four stanzas, and the last line of each stanza contains the name of the village where each priestly family resided. This is the key to understanding Avi-Yonah’s reconstruction of the Caesarea inscription (see Fig. 4, below) for, with this knowledge, it is theoretically possible to determine the village in Galilee where each priestly family was stationed.

Here, then, is what one reads at the end of the 18th stanza of ha-Kalir’s lamentation, the stanza corresponding to the priestly family of Hapises:

ובקצוי ארץ נזרת

משׁמרת נצרת

And to the ends of the earth was dispersed

The priestly class of Natsareth

This is why Avi-Yonah reconstructed the eighteenth line of the inscription as follows:

The 18th course Hapizzez NAZARETH

Proceeding in an analogous manner it is possible to reconstruct the other lines, by analogy between the four stanzas of Kalir (17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th) and the four corresponding lines of Fragment A (photo Fig. 2; reconstruction Fig. 4).

The last line of ha-Kalir’s 17th stanza (for the family Hezir) has the village Mamliah; the last line of the 19th stanza (for the family Pethahiah) has the village Arav (Arab); and the last line of the 20th stanza (for the family Ezekiel) has the village Migdal Nunaiya.

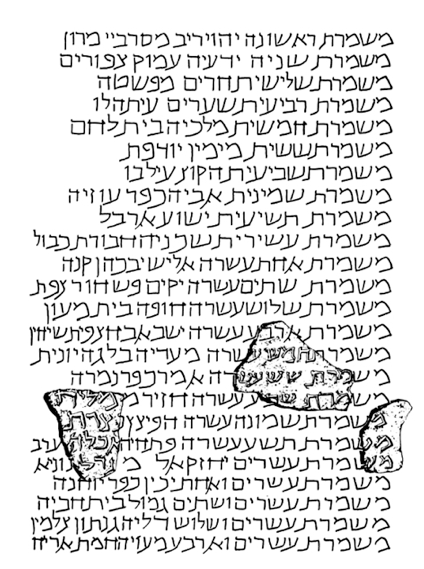

![Fig. 2. Fragment A (left) containing the words [M]amliah, Nazareth (נצרת second line), akhlah, and [Mi]gdal, corresponding to lines 17-20 of the list of priestly courses and their residences. Fragment B is to the right.[Note the difference in size of the Hebrew letters, in line spacing, and in character of the chiseling from one fragment to the other. These problems will be considered in a subsequent post.—R.S.] Taken from Ameling et al, p. 66.](https://www.mythicistpapers.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/A-+-B-Tucc-1024x607.png)

Fig. 2. Fragment A (left) containing the words [M]amliah, Nazareth (נצרת second line), akhlah, and [Mi]gdal, corresponding to lines 17-20 of the list of priestly courses and their residences. Fragment B is to the right.

[Note the difference in size of the Hebrew letters, in line spacing, and in character of the chiseling from one fragment to the other. These problems will be considered in a subsequent post.—R.S.] Taken from Ameling et al, p. 66.

Fig. 3. The lost (and largest) fragment C from a photo published by S. Talmon in 1958. It apparently contains parts of lines 15-17 of the list of priestly courses.

Fig. 4. The Caesarea inscription as reconstructed by Avi-Yonah.

[Fragment C (top) is lost. Fragments A and B supposedly begin and end the same lines of text, while fragments A and C share the same line of text. Thus, it is eminently possible to compare the writing on the fragments—the orthography, spacing of lines, size of letters, and manner of chiseling—with a view towards compatibility. It is also possible to compare the composition, thickness, and color of the two surviving marble fragments A and B.—R.S.]

______________________________

Footnotes:

6. Ha-Kalir lived in the early part of the seventh century CE at the earliest (Taylor 36; Klein 1909:5 and 1923:47-48). A piyyut (pl. piyyutim) is a liturgical poem generally intended for singing or recital. The Lamentation for the 9th of (the month of) Ab (July-August) commemorates the date of the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in the year 70 CE. It is part of a composition by ha-Kalir entitled Ekha yashebah habaseleth ha Sharon.

7. Another consideration concerns Mamliah—the Galilean village and residence of the priestly family Hezir. In the Lamentation we find it written as ממלח and this was the normal form of the village’s name in rabbinic literature. Yet we find the word in fragment A with a iod between the lamed and the ḥeth (ממליח). Is this reading admissible? Yes, according Uzi Leibner (2009:175, n. 44)—but his chief evidence is the now controversial Caesarea inscription.